With Christmas just a couple of days away, it’s a good time to take stock of the shopping season. I think a fair bit about the luxury retail market, because where the rich lead, the market — and even the economy as a whole — tends to follow. This past year was the worst for the luxury industry since the great recession of 2007-09.

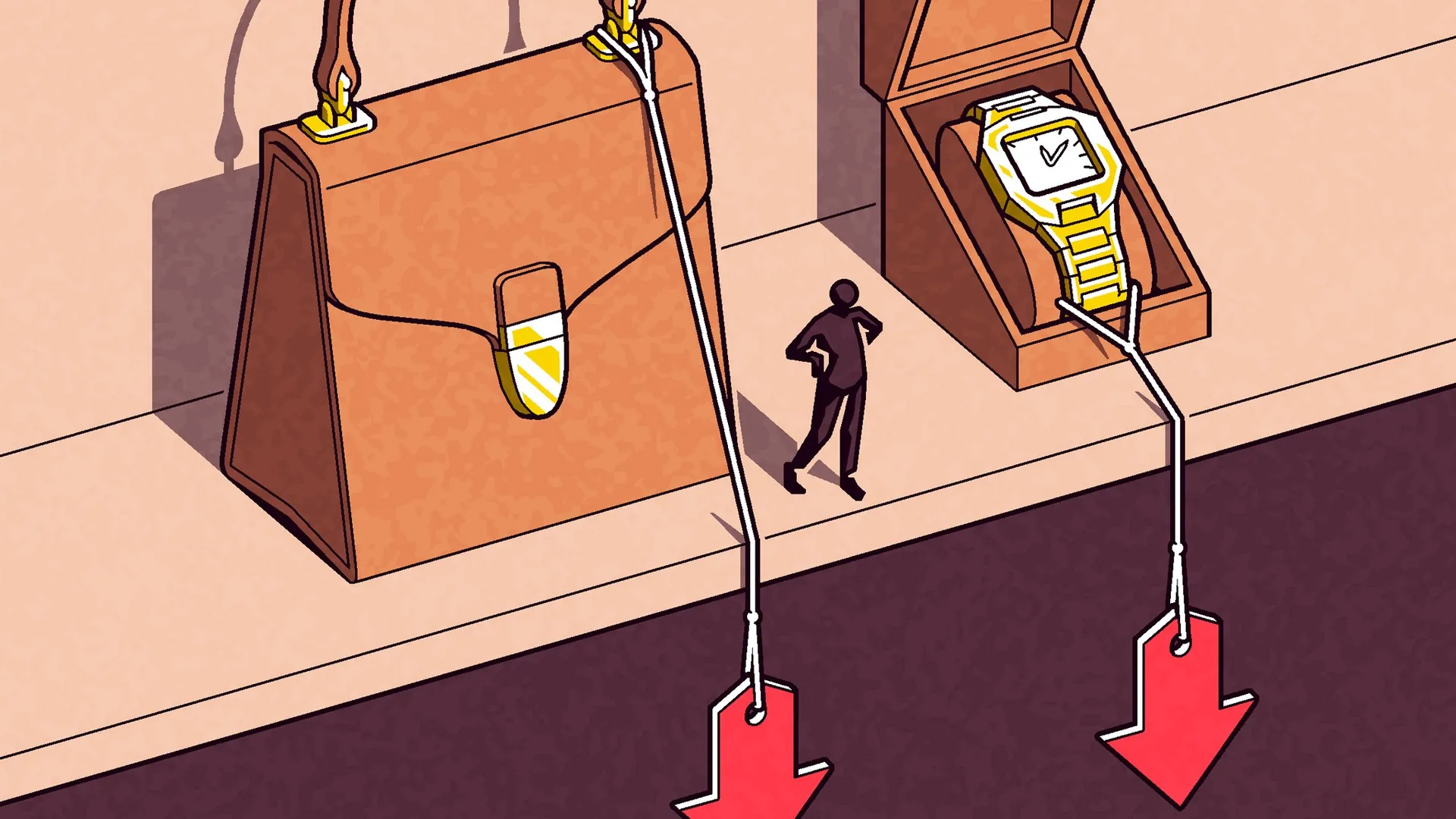

While the super-rich are still spending as if they exist in a separate gravitational orbit, the aspirational consumers who make up the all-important “mass luxury” part of the market are scaling back. That goes a long way to explaining why many of the world’s largest luxury companies have underperformed recently. There are, after all, only so many watches and handbags that the one per cent can buy.

And the number of people who can afford this sort of thing is declining. The latest Bain luxury market report, released in November, found that the luxury market shrank by about 50mn consumers over the past two years, in part because younger consumers are turning away from traditional luxury goods. I suspect that this is one of the reasons you are (finally) seeing older people, particular older women, in advertising and even on fashion runaways. They are the only people buying stuff.

But there are other reasons that luxury has lost its lustre, notable among them the pervasive feeling that economic insecurity may be around the corner, despite buoyant markets.

If you discount the V-shaped Covid blip, we are six years overdue for a recession. Meanwhile, the bizarre world of the US equity markets, which are priced for perfection, has everyone at New York dinner parties talking about when (and if) they are planning to take at least some of their portfolios to cash.

Despite this, or perhaps because of it, the super-rich can still spend. Those in the ultra-wealthy segment of the luxury market — meaning the people who spend their excess cash on yachts and jets (both sectors which are doing quite well) — have seen their net worth bolstered by double-digit asset market growth. There’s big fleet expansion in the super high-end cruise business, and growth in luxury cars and hotels is still strong.

But less wealthy people who were once ready to splurge on that $500 handbag are being far more cautious. That’s because they, unlike the super-rich, still have to worry about working. Aspirational consumers’ disposable incomes are down, having been affected by reduced job openings and increasing voluntary turnover rates, according to the Bain study. That’s why overall luxury sales are expected to drop by about 2 per cent in 2024, and remain flat next year.

So what does all this tell us about what’s to come in the broader economy in 2025? There are three key lessons.

First, a US equity market correction will come, perhaps this year, perhaps next. But few rich people I speak with have any doubt that it’s on its way. The fact that even the affluent are scaling back purchases of fine wines, jewellery, watches, and art means that a lot of asset-wealthy consumers are expecting a slowdown and some kind of market correction, even if we don’t see a full-blown trade war.

Second, if the latter did come to pass, the luxury sector, which is dominated by high-value European goods, would fall much faster and harder than other areas. Europe doesn’t have tech giants, but it has luxury conglomerates — two out of the top five largest European firms by market capitalisation are LVMH and Hermès.

One could easily imagine the products these companies make becoming targets for tariffs if Trump turns a critical eye to the continent. Remember when the EU retaliated against Trump’s steel and aluminium tariffs by putting tariffs on motorcycles, adding $2,200 to the price of a Harley-Davidson? European luxury brands — including German automakers and French fashion houses — would be easy political pickings.

Finally, there’s a growing sense in the luxury business that some of the price inflation we’ve seen over the past several years simply can’t last. Already, only the top name brands in any given category of personal luxury can hold their price points, as aspirational clients downshift to cheaper watches or spirits.

Ditto travel and leisure. I recently spoke to two private equity investors in the hotel business in the US who predicted that while top-notch markets such as Jackson Hole, Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard would probably be fine in a downturn, nosebleed rates for rooms at a four-star hotel in Houston on a Tuesday night would come down at the first sign of a market correction.

For those of us who’ve noticed that $500 seems to be the new $300 for hotel rooms in major American cities, that’s welcome news. But as we wait for rates to fall, there’s always the small splurge on a high-end beauty item.

The “lipstick index,” a term coined by beauty titan Leonard Lauder, posits that when purchases of small luxury items like a new cosmetic go up, a recession is imminent. In 2024, beauty was one of the few luxury categories with positive growth, as consumers sought out that small splurge.

If my husband is reading this, I’m hoping for a tube of Celine’s Rouge Triomphe in the stocking.